Cave paintings and a shift in perspective. Namibia - Part 1

We humans have a propensity towards falling victim to labels, and then we start navigating life through this lens, often at an unconscious level. If, at some point, we do become conscious of these sticky imprints, we may spend another lifetime reclaiming our blueprint. We also realise, in the process, that the harder we fight it, the more stubborn it becomes. So how do we ease into it, how do we reconcile and befriend all these identities that make up our being? How do we integrate, in a felt sense, the fact that all of them and none of them define us?

Insomnia has been such a big presence in my life since I was 18, that it became an identity. A narrative that I’d keep on playing in my head and to others, often in an attempt to justify myself for any potential failure or inability to perform at 100% (in any situation, whether personal or professional). Perfectionism at its best. What I would also do, though, was to sabotage myself to a point that I’d keep myself small through it, and, as I realise it now, I’d use it as some sort of a shield against taking too much space in the world.

Sometimes, it only takes a random encounter to put everything in a different light.

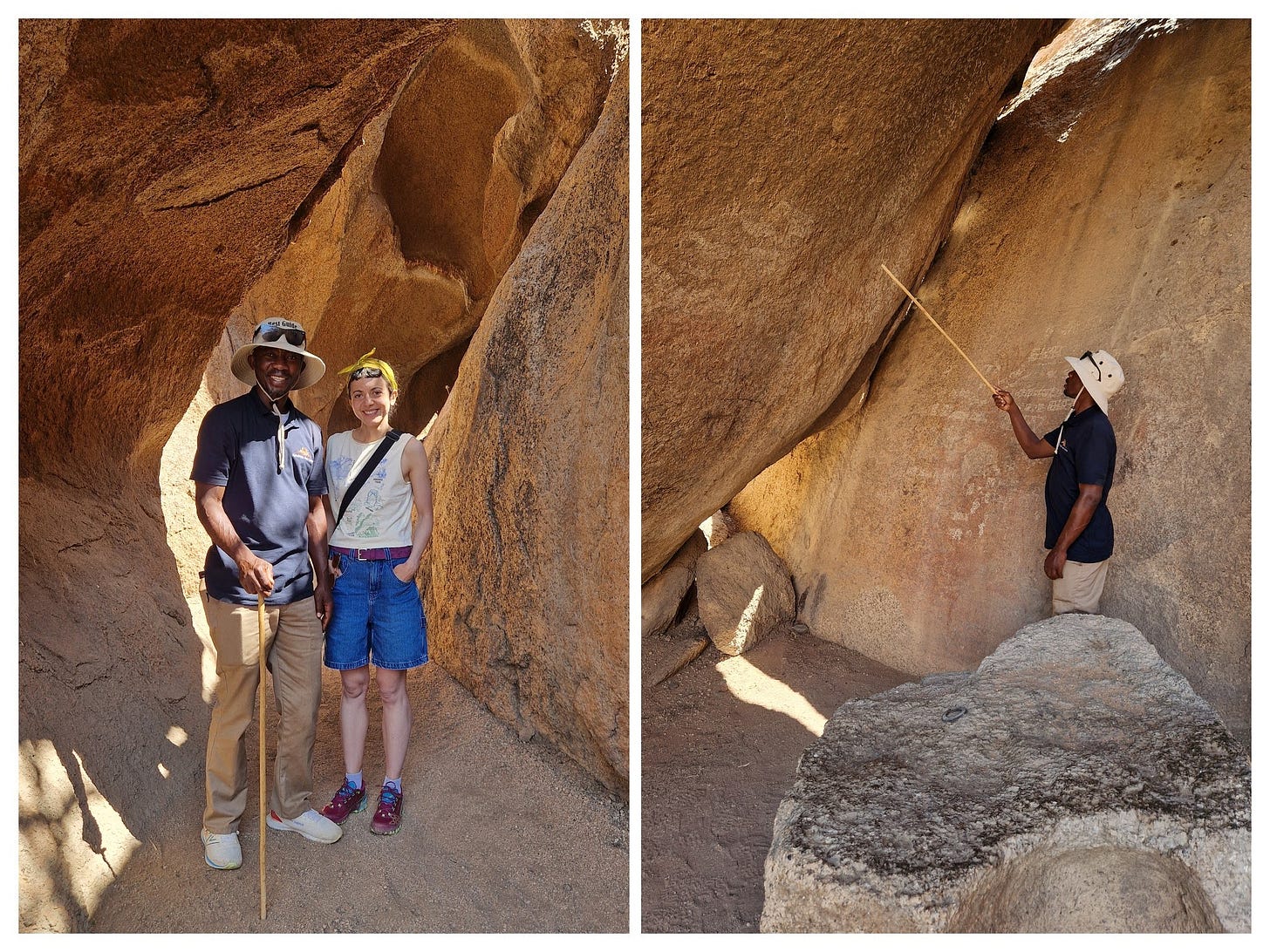

One of the most truthful and insightful encounters we’ve experienced in Namibia was the guided tour, turned private and way longer than initially planned, around the cave paintings in the Spitzkoppe Nature Reserve. Our guide, John, a slender and talkative, yet wise and perceptive man, offered us what we always hope to experience during a trip - a genuine and soulful insight into the richness of a landscape, with all its demons and beauty, light and shadows. There’s some beautiful recollections of the presence of the Khoisan people - foraging bushmen and indigenous population originally from South Africa and who later migrated to other parts of Africa - on the impressive boulders in Spitzkoppe. The depiction of these past realities is both elaborate and intuitive, easy to grasp. The hunter gatherers made use of their creative skills and wisdom to communicate. A fish pointing to the sea or a rhino’s horns indicating a nearby body of water were offering intuitive yet clear directions to the people in their tribes. Another thing that caught my eye was the detailed and accurate representations of wildlife, in contrast to a more simplistic, almost stick-like portrayal of the humans, to me a true testament of the indigenous communities’ deep connection to the natural world.

Our discussion also played so well on my artistry and fascination with indigenous face and body painting. Hearing about all the natural materials that the hunter gatherers used to paint on the walls - everything from red ochre pigments and egg white, to animal blood, poop and fat - was music to my ears and stood as another witness to their strong bond with and knowledge of the natural world.

And did you know that white rhinos have different characteristics from black rhinos? The most significant distinction is the shape of a rhino’s mouth and lips, which directly impacts their diets. White rhinos are grazer, so flat and broad lips serve excellently to the purpose, whereas black rhinos feed on leaves and branches and, accordingly, their lips shape has evolved into a pointed lip (with the shape of a hook) to be able to grab hold of the trees. A white rhino will usually have a longer front horn and a much shorter second horn. The two horns of black rhinos are more similar in length. And legend has it that the contrast between the two rhinos mirrors the one between caucasian and indigenous women, particularly in the way they carry their babies - the former carrying or leaving their children walk in front, while the latter carry their babies behind.

Fast forward into our engaging chats, as we had been building mutual trust and genuine curiosity, we reached a point where we’d pierce into more personal life experiences, also touching on cultural differences, values and belief systems. I really enjoyed the stories John shared about the shift in his relationship with spirituality, as he would learn to make his own sense of a fractured household - a parent with a Christian view on life (and death, for that matter), and one who was fully immersed in the traditional, indigenous belief system of the Himba people. His parents split when he was a child and he would live with his mum throughout a big part of his young self. Their relationship was complicated, as John would rebel, to the point of denying his spiritual nature rooted in indigenous practices and wisdom, that his mother strived to instil into him. He would dismiss this way of living in close connection to the land and spiritual practices as boring and purposeless, and he would rather be with his father and use his intellect in school. Gradually, he would start to embrace and deepen his relationship with his soul and spirit, and become aware of his body as a messenger of his life’s purpose. As I could sense it from his stories, this awakening to his truth took an even more palpable shape when he suffered a stroke in his late 30s, an experience from which he hasn’t physically fully recovered, 4 years into it. Out of all the details of John’s rekindling love and connection to his indigenous roots, there was one in particular that sank in the most, one that, after some time of processing, felt like a soothing revelation. He remembered how he used to often wake up during the middle of the night, at around 3am, and couldn't put himself back to sleep after that. He wouldn’t know what to make of it back then, yet later on he would associate these midnight wakings with the exact same thing that he would rebel against his entire childhood - his spirituality.

The shamans were much valued and honoured figures within the indigenous communities. They would initiate women into the sacredness and healing power of plants, and perform various rituals for the men in the tribe. All these ritualistic practices happened during the night, as that’s when it’s believed the spirit is awake, whereas the physical world, as well as the physical body, belonged to daylight. John’s recalling of his sleepless nights reminded me of my own, but also of my struggle to not just understand and heal these burdening patterns that hindered me to be fully present in my life, but also to find any form of meaning in it. Where after many years of therapy I did find a (rational) answer towards why I had such a hard time to allow sleep to exert its mind-body-soul healing power - which was an extraordinary revelation in itself - frustration lingered and I allowed it to become bigger than me, like a stigma I carried with me everywhere. This, in turn allowed the insomnia to always come back, sooner or later, at an intensity that often knocked me down.

It was from that space of curiosity and human connection with another wandering soul that this serendipitous moment emerged. All these beautiful and hopeful questions started popping into my head. What if this restlessness is actually a process of awakening to my essence? What if there’s much more spirit, wisdom and creative freedom in myself than I allow myself to believe there is? What if I am much more attuned to the hunter gatherer’s way of living and to their connection with nature, than to what modern life is asking of me to be? I’ve always had a sense that for me, being a homebody means being in nature, and that all these fears I have are not actually mine, but part of the same belief systems and dysregulations that got me into perceiving insomnia (insert your own struggle here) as something being wrong with me. What if this is the Universe’s way to propel me towards reclaiming my wild nature?

Do I have a concrete answer to these questions at the moment? Not really. But does it really matter in the end? Very often, the answer is in the question itself, especially if it’s a question that sprouts from a serendipitous, yet as close to reality as possible, moment like this one. For me insomnia is a lot about (not) feeling safe in my body and my environment, as a result of living in a constant alert mode throughout my childhood and particularly my adolescence - hence also the anxiety, the need for control and perfectionism which directly influences my relationship with sleep, that I carried with me in my adult life. I’m (still) in a process to embody all the insights I’ve gained, all the practices I’ve learned along the way that help me bring my nervous system to a place of balance and safety, yet this encounter with John made me look at these patterns with curiosity, and this, in turn, gives insomnia less power.

And I wonder if the solution to shaking off and letting go of continuously pushing this boulder up (Sisyphus is my middle name), is the same solution that would heal most of this modern’s world ailments, disasters and uprootedness, and that is relearning how to create and be in communities in a way that feels rooted and genuine. Hunter gatherers used to take turns to watch the fire during the night that protected them from (real) dangers. With individuality on the rise, we stopped doing that, and in turn we don’t trust our intuition or allow ourselves in the hands of others anymore. Sure, there’s no more fire to keep an eye on, so we can protect ourselves from potential attackers, yet there’s so much we could benefit from having communities around. And one consequence of this solid ground being swept away from under our feet, is that we’ve lost the ability to perceive real danger from imaginary one, which keeps us in a perpetual state of hypervigilance and disconnect.

John’s connection to both worlds made him into the adult he is today. School and education gave him a degree that brought along a sense of power in a society with a long history, that continues to the day, of suppressing and outcasting indigenous and nomadic populations, while his ancestral roots keep him grounded and in a profound relationship with the natural world. John is a healthy embodiment of the fusion between these two worlds, as he is using his knowledge to not only educate people about ancestral wisdom and rituals, but to also infuse a sense of who we are as human species in relation to mother nature, how much we depend on the health of this ecosystem, and how disconnected we start to live once we move away from our soul’s calling and from communities.

Sparks of interest:

The many magical encounters with the elephants in Namibia reminded me of The Elephant Whisperer, a book that touched me deeply and taught me so much about these majestic and wise creatures.

A mouthwatering Sweat Bean paste and an eye watering, bittersweet story, brimming with humanity and exploring themes of loneliness, social stigma and finding one’s purpose.

A favourite quote from one the most beautiful podcast episodes I’ve listened to: “There is a place in the soul that neither time nor space nor any created thing can touch. And I really thought that was amazing. And if you cash it out, what it means is that your identity is not equivalent to your biography, and that there is a place in you where you have never been wounded, where there is still a sureness in you, where there’s a seamlessness in you, and where there is a confidence and tranquillity in you. And I think the intention of prayer and spirituality and love is, now and again, to visit that inner kind of sanctuary.” John O’Donohue, The inner landscape of beauty

Some relevant and insightful Career Advice for Filmmakers, yet applicable for most creatives in the industry.

A study on how Chimps and Bonobos reveal the best and worst of us.

The reason why we are feeling so wired and tired is obvious. But is it?

As a reiteration of one of the topics I touched upon in my story above, here’s some more evidence on how living in a commune could be the cure for society